The month gets off to a good start. A longstanding client has confirmed that a big project will be going ahead. The job involves producing bilingual content for a section of the corporate website, a kind of online museum. It will be a bit different from my usual work. I will be copywriting into English from a Spanish brief, and coordinating the rest of the project: translation of English copy back into Spanish, editing in both languages, terminology etc. I’m looking forward to the variety, and to putting together a team of colleagues. And it provides me with a degree of security for the rest of the year. After a little discussion, I agree a frankly unrealistic deadline, fairly confident that the bottlenecks will be at their end rather than mine.

On 13 March we get the news we have all been dreading, expecting and perhaps hoping for. As the numbers of cases and deaths rise, Spain has declared a state of emergency in an attempt to curb the spread of Covid19. Although the epicentres are in Madrid, Barcelona and the Basque Country, a lockdown has been imposed in Andalusia too. My own feeling, I confess, is one of relief. This suspension of normality is strangely welcome. My own normality was suspended last summer when my wife and I separated. For the last nine months I’ve been living a divided existence: half of the time in the family home with my kids and my dogs, the other half unrooted, back in Scotland or in a rented flat nearby. I’m not sure what I’m doing here, in my ex-wife’s home town. I need to make plans for the future but I am still clinging to the past. Our flat has become the setting for a peculiar French farce of modern family life. Once a week I exit stage left when my ex arrives; a week later the process is repeated in reverse to mark my return. This is not so much co-parenting as part-time single parenting. I’m at my best when I’m with my kids: I feel grounded, accompanied, I know who I am, I have a purpose. But the solo periods are more difficult. I am too distraught to enjoy my freedom, a heartbroken bachelor rattling around in his pad, the space filled with the lustrous green of cheap houseplants from Lidl, my time filled with translation. Thankfully, I can translate in almost any emotional state. It is, if not therapy, then at least a soothing balm.

The suspension of time, this feeling of the rest of the world coming into synch with my own private catastrophe, has an unexpected effect. I am momentarily energized. During the first week of lockdown, I write a short story. In Spanish. The choice of language is pragmatic. My playwright friends are all writing short pandemic-themed dramatic monologues – in Catalan or Spanish – and I want to join in. But writing in this language – which is not “mine” – is constraining and thus, paradoxically, liberating. I am restricted, I have less range, a smaller vocabulary, less control over different registers, less ability to step outside of my own idiolect into the wider language beyond. I find myself in a linguistic lockdown, essential purchases and dog-walking only, a simplicity that allows my writing to flow.

I finish the piece and share it with my colleagues. Normally, I channel their writing from Spanish into English: they write, I translate. Today, I have broken the rules. I am writing, not translating. And I am doing it in Spanish, not English. In translation, I reveal very little of myself. In writing, I can reveal as much as I want.

Writing in Spanish, though, throws up another problem. Most of my writing is not published in the traditional sense. I post it on my website and then share it via social media or email. This is a piece I would normally share with friends and family but by writing in Spanish I have created a barrier. And so I must become a translator once again.

Near the start of the piece, my son jokes about how we should deal with people who have brought the virus to Cadiz from Madrid as they flee to their second homes on the coast:

Si escuchas a alguien decir ‘tronco’ por la calle, mátalo ya, quillo.

[= If you hear someone say tronco when you’re out and about, just kill them, quillo]

Quillo is short for chiquillo and is a typical Cadiz term, equivalent, roughly, to ‘mate’ in English. Tronco is a Madrid alternative, somewhat old-fashioned now, the kind of word you might hear on a TV drama set in the Spanish capital in the 1990s.

How do I translate this shibboleth test into English? I can’t leave the words in Spanish but nor can I replace them with English equivalents. In the end, I settle for a non-lexical version:

If you see someone in a Real Madrid top, just kill them.

It’s a clever solution, I think, but I can’t help recognizing that something – rather a lot, in fact – has been lost. My little story is, among other things, about a relationship to place and to language, about how identity changes but is always local. Not much of this is captured by the Real Madrid shirt.

There is more loss to come. Halfway through the story, I have come back from the newly cordoned off beach, my morning dog-walk frustrated, and decide to take the dogs up onto the roof to give them some exercise. I worry about keeping the animals under control as I make my way upstairs with the laundry, a cup of coffee and some home baking:

The bag is too big, the coffee will spill, the dogs will go crazy on the stairs.

But here, too, something has gone astray. In the original I wrote not that the dogs would “go crazy” (volverse locas) but rather, se van a desmadrar. Literally, they will become unmothered. There is no such word as “unmother” in English, which is, no doubt, one of the reasons why I like it so much in Spanish, its lack of a direct equivalent making it more vivid, more salient, a fresh image for my non-native mind. It is not, though, the dogs who are in danger of becoming unmothered but rather my children, who have been alternately unmothered and unfathered on a weekly basis for the best part of a year and for the foreseeable future.

Of the many silly things that are said about translation, perhaps the silliest of all is the insistence that nothing is untranslatable, the reluctance to acknowledge the inevitability of loss. But translation, like life, is, among other things, a process of managing loss. Sometimes, often, that loss may feel negligible or may simply be outweighed by what we add. When I translate a rambling, verbose piece of academic prose into clean, flowing English, I am confident that my version is better than the original, that I have cast the author in a better light than, perhaps, he deserves, that there is little loss and much gain.

Sometimes, I prefer to think less in terms of loss and gain than of change. I refuse on principle to produce ‘literal’ translations of stage plays. My theatre translations always invoke a version of the play, a production that takes place inside my head as I translate. I do whatever is necessary to make that work, to give the characters their voices, to mark the rhythms of the drama, to exploit the potential offered by the target language. There is loss here too, to be sure, but so much more change and transformation that I don’t need to dwell on it.

In other cases, more perhaps than we care to admit, it is the loss that dominates, at least during the process of translation. Maybe, after it is done, we will be able to look back, to appreciate the necessity of change, the inevitability of loss, to appreciate, even, the silver lining of those little gains and the new thing that has been created.

The second half of March brings news of the postponement of a couple of projects. One of these is a regular report on the state of the European Union. The client has already invested in the writing stage; translation is a small part of the overall budget and without it everything else will have been a waste of time and money. I’m fairly confident that this job will resurface later in the year; perhaps, if I’m lucky, it will coincide with a quiet spell. I’m more disappointed about the other project. It was a comic about women scientists, my first full-length comic translation, my first job for a new client. For the moment it has been put on hold but I suspect this job won’t resurface. It’s hard not to worry about the pandemic’s likely impact on work – and I feel more grateful than ever for that large copywriting project.

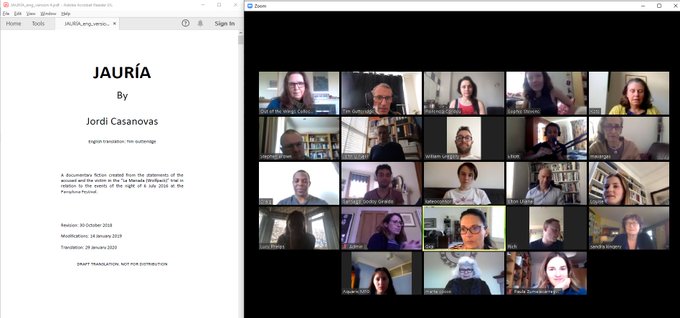

At the end of March, I have a reading of my translation of Jauría (the documentary drama I translated in January about the Manada gang rape case). The reading takes place under the auspices of Out of the Wings, a London-based collective for theatre translators working between Spanish and Portuguese and English.

Screenshot of Out of the Wings Zoom reading of Jauría

Out of the Wings member, William Gregory, deserves the credit (or the blame!) for getting me involved in theatre translation. It’s the least lucrative but most enjoyable part of what I do and, for the moment, I am trying to create a portfolio of work and use that to build up a network of contacts in the hope that, at some point, my addiction to translating dialogue will start to pay for itself.

The reading was originally due to take place in London but has now shifted online. The script is read, via Zoom, by a cast of professional actors, and the reading is followed by a discussion by the members of the collective and anyone else who wants to attend. Perhaps surprisingly, for me the main benefit of participating in a reading such as this is not the opportunity to revise my translation in the wake of hearing it performed. I make few if any changes at this stage; at most, the odd minor infelicity that has slipped through. I’m perfectly happy, though, for directors and actors to make whatever changes they deem necessary. Each line of translated dialogue ceases to be work in progress when I settle on a version I like. For some lines, most even, that happens at draft one; for others, it takes a little longer. But I think that this letting go is, really, a recognition of the collaborative nature of translation. The collaboration is asynchronous but it is essential to the process. What else is a translation but a collaboration between translator and author, regardless of whether the author has any direct involvement (answering queries or resolving doubts) or is even still alive?

In theatre, there is an acceptance that the finished script (whether translated or not) is merely the basis for a further collaboration, between director and actors, which has as its result a performance on the stage, in which the collaboration occurs between actors and audience.

The collaboration is less immediately apparent in written translation – there are no collective spaces to parallel the rehearsal room and the stage. But it is still there: between the translator and the author; with the involvement of publishers, agents, editors and proofreaders; and, finally, between all of these and the reader. I wonder if the translator’s (or the author’s) frequent reluctance to let go of a final text is part of a denial of this collaboration, an insistence that they and they alone have created the text, a delusion of control over how the text will be experienced and, hopefully, enjoyed.