We are two weeks into lockdown and I have the sense that work is slowing down around me, although for the time being I have plenty to keep me busy. For this month, I have some edits to incorporate, two more paid samples to translate, a romantic modernist poem to produce, two short stories for young readers as part of an academic project comparing the reception of bowdlerized versus “warts and all” versions of the same text, various bits and pieces for regular clients – and my big corporate copywriting job.

I’m slightly worried about immersing myself in project management and admin, given both the general circumstances (there is no end in sight for Covid19) and my own personal situation. I am aware of my ambivalence not just towards the nitty-gritty of it all (file management, endless emails, budgets and schedules) but, perhaps more than that, towards what it says about me. I am actually quite good at this activity that also makes me feel anxious and, occasionally, bored. I am like an anarchist with a guilty yearning to be a traffic warden.

As the project gets going, though, I remember why I was drawn to it. I put together a small team – a close friend and colleague who lives round the corner, and two fine Spanish translators, neither of whom I have ever met in person. I will split the English copywriting with my friend and we will review and edit one another’s work. This friend is self-taught and works almost exclusively for one client, a news service. As far as the wider translation community is concerned, he might as well not exist. And yet he is one of the very best translators I know. By contrast, last year, I did a line-by-line comparison of the first chapter of a high-profile translation (a literary novel that was also a bestseller). It was more or less readable but closer inspection revealed a mixture of clumsiness, omissions and a sprinkling of basic errors. Needless to say, it was the work of a highly-regarded translator. (One reviewer acerbically noted that the book had found the translator it deserved, although I’m not sure that any book deserves to be badly translated.) This is one of the supremely odd effects of the public/private nature of translation. It’s as if you could go to the Nou Camp to see Messi play, only to find that he is not just having an off-day but is simply not very good. And then you wander down to the local park to watch a Sunday league game and realize that the bald guy in midfield is as good as anyone on the Barcelona team (and certainly streets ahead of that overrated Argentinian bloke).

Lockdown creates a strange rhythm, heightening the polarization of my alternate weeks of being with and without my kids. When I am on my own, I have limited opportunities to leave the flat. I bring one of my dogs to the bachelor pad in order to have an excuse to break the curfew, I drink coffee on the balcony and beer on the roof. And I work. When I am with the kids, lockdown softens. I am back in the family flat, I have two dogs, plenty of shopping expeditions and, best of all, the company of my children (who are studying from home). Work is lower on my list of priorities.

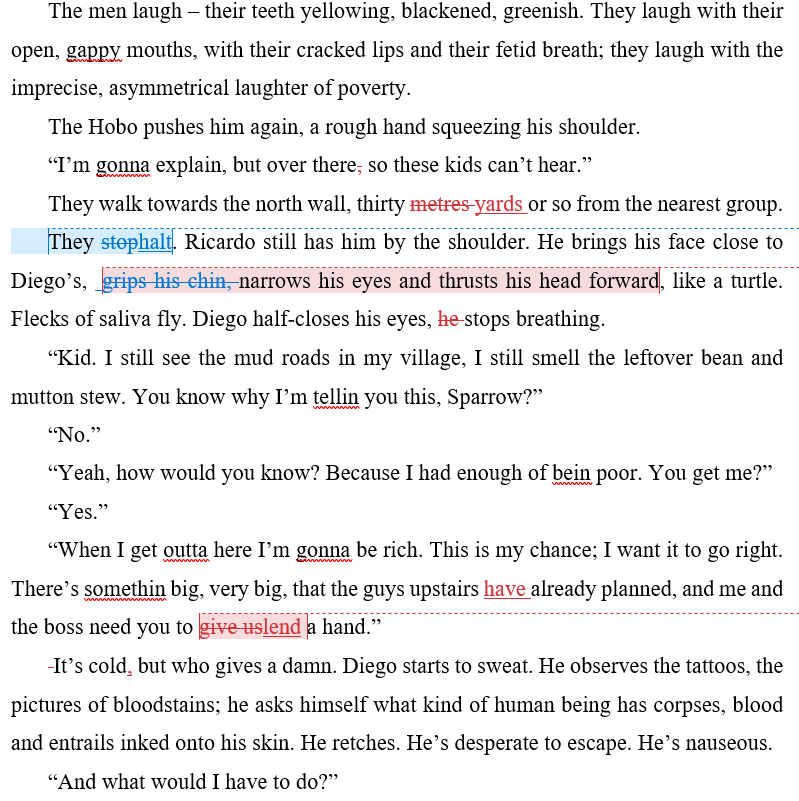

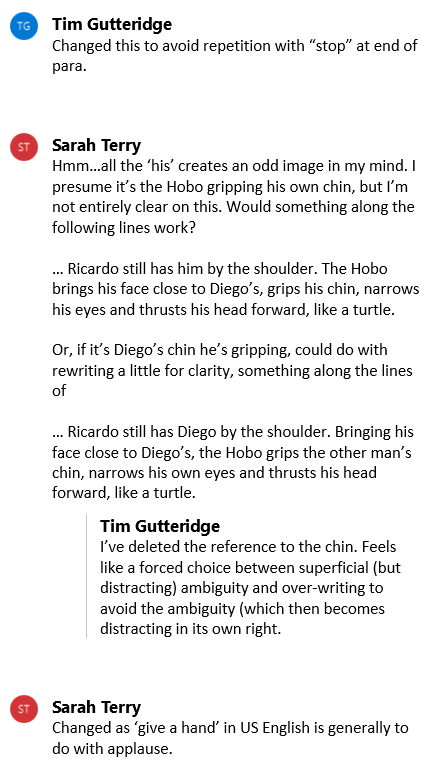

This week I am going through the copy editor’s changes, suggestions and queries on the manuscript of Crocodile Tears, the Uruguayan thriller I finished translating in January. Translators seem to have mixed feelings about being edited. I don’t know if this reflects bad experiences, insecurities or their attachment to the illusion of control and the artistic endeavour as individual pursuit. I always enjoy being edited, I pride myself on the fact, even. Although it occurs to me that perhaps it is not such a virtue, that my enjoyment may draw on a certain arrogance or even reflect a deep-seated need for attention (satisfied, in this case, through being the target of copious tracked changes and extensive comments in Microsoft Word). Whatever the motive, the edits on Crocodile Tears are a pleasure to go through. Bitter Lemon Press have assigned Sarah Terry to edit the manuscript. I used to be a copy editor myself. I was bad enough that I stopped doing it. But not so bad that I can’t recognize the work of someone who is really good. Reassuringly, there are very few errors in my translation as such, just lots of points where the editor has spotted opportunities for improvement or identified possible snags.

I take most of them on board either directly, by incorporating the editor’s suggestion, or indirectly, by making some other adjustment instead. Sometimes I slice through the Gordian knot and just delete whatever word is causing the problem. It’s important to be able to let go of something in the source text if the price of keeping it is too high.

In addition to providing the chance to carry on improving the text (when I’d exhausted my capacity to improve it on my own), the editing process is really the first external read of my translation. It’s like having a long, rambling conversation about my work with an intelligent, attentive reader.

This month’s paid samples, again with that all-important public funding, are from two non-fiction titles, a category for which I much prefer the Spanish term ensayo, although I’m always slightly disconcerted when such books with a strong personal narrative are referred to as novelas, as they occasionally are. (Have I misunderstood the Spanish terms or has the reviewer not actually read the book? I am never quite sure.) I am translating the first chapter of El analista, Txema Guijarro’s inside account of the political, legal and media storm that surrounded the Snowden and Assange affairs. And I’m also working on an excerpt from El director, David Jiménez’s account of his time as editor-in-chief of Spain’s El mundo newspaper, which has since descended into the gutter and abandoned any pretence of serious journalism.

I enjoy the way that translating non-fiction requires a constant negotiation between the world of the text and the ‘real’ world outside it. How much adjustment – addition, omission, explanation – does the translator need to provide to make the book work for the target audience? Making those adjustments in an unobtrusive but effective manner requires a lot of craft, and is every bit as challenging as translating literary fiction or drama.

I’m also enjoying the stylistic demands of this particular text. The author, Jiménez, was a foreign correspondent who was unexpectedly appointed editor-in-chief of the paper, the owners presumably hoping that his political naivete would make him easy to manipulate while also providing them with cover for their plans. The style, like a lot of the best journalism, draws its energy from treading the delicate line between muscular reportage and cliché. When translating, I strive to do the same. If I obey George Orwell’s dictum (“Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print”), I will flatten the text and destroy the synergy between subject matter and style. If I go too far in the other direction, reaching for fixed phrases and common collocations at every opportunity, I will produce a deadening caricature of the original.

El despacho del director de El Mundo había sido en todo ese tiempo uno de los mayores centros de influencia del país, cortejado por reyes y jueces, ministros y celebridades, escritores y cantantes, caciques y conseguidores.

Here, for decoding purposes, is the DeepL machine translation:

The office of the director of El Mundo had been in all that time one of the biggest centres of influence in the country, courted by kings and judges, ministers and celebrities, writers and singers, chiefs and procurers.

And here’s my take on it:

Throughout that time, the office of El Mundo’s editor-in-chief had been one of the country’s nerve centres, a place visited by kings and judges, ministers and celebrities, writers and singers, party bosses and men in grey suits.

El país vivía, además, el momento de mayor tensión política desde la transición a la democracia, con una economía herida, una elite que se aferraba atemorizada a sus privilegios, nuevos partidos que amenazaban el orden establecido y unos medios de comunicación en su mayoría arrodillados ante el poder, que había aprovechado nuestra fragilidad para organizar el mayor y más coordinado ataque contra la libertad de prensa desde el final de la dictadura del general Franco.

Again, the DeepL machine translation version:

The country was also experiencing the greatest political tension since the transition to democracy, with a wounded economy, an elite that clung to its privileges in fear, new parties that threatened the established order and a media that was mostly on its knees in the face of power, which had taken advantage of our fragility to organise the biggest and most coordinated attack on the freedom of the press since the end of General Franco’s dictatorship.

And my translation:

To make matters worse, Spain was in the throes of its greatest political crisis since the transition to democracy in the late 1970s. The economy was floundering, the elite were clinging grimly to their privileges, new parties were threatening the established order – and most of the media were pandering to those in power, who had seized upon the sector’s weakness to launch the largest, most coordinated assault on press freedom since the death of General Franco.

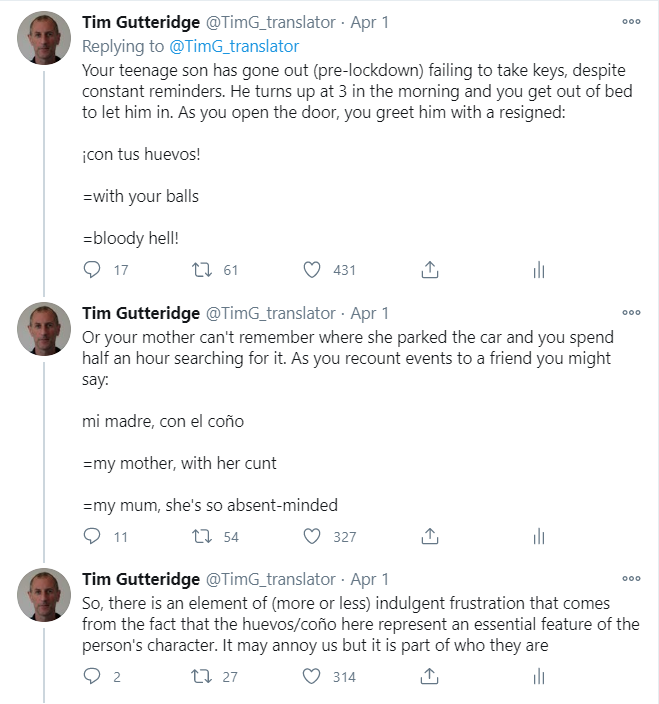

Like a lot of people, I have a love–hate relationship with social media. I’ve pulled back my presence on Facebook, in particular. However, I still enjoy the way that Twitter, at its best, provides a platform for discussing translation, a place where I can share bite-sized examples of my work, ask for help, connect with colleagues. Under lockdown, I’m very much aware that Twitter is a double-edged sword. It’s a vital window onto the outside world, a place where I can have conversations on days when, perhaps, I won’t meet anyone in person. It is also, though, an unwelcome source of news and rumour and speculation, all of which overloads me and makes me feel anxious.

Doomscrolling apart, another thing I like about Twitter is that it’s a place where Spanish and English merge, and I often combine the two languages in the same tweet or thread, particularly when I’m tweeting about my work. It’s always fun to write about non-obvious translations and I really enjoy engaging with both translators and non-translators. This month, I publish a long thread on the way Spanish daily usage is peppered with (not particularly rude) references to genitalia, showing both literal and pragmatic translations.

The thread goes viral, with 12,000 likes and well over a million views. I have also picked up around 1,000 new followers. Apparently there is an audience out there keen for as much bilingual smut as they can find.